As much as digital archives promise to make cultural materials accessible to broad audiences, they also present a danger of repeating the power structures that are implicit in the way many Western archives have traditionally been structured. In her talk Thursday, Elizabeth Maddock Dillon discussed a project that is attempting to avoid this reinscription: the Early Caribbean Digital Archive. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s analysis of the archive as a means of knowledge production and on Ann Laura Stoler’s work on the epistemologies implicit in colonial records, Dillon made a case for a form of archive that deemphasizes the figure of the author, while encouraging a consideration of the complex relations between people, texts, and historical events.

As much as digital archives promise to make cultural materials accessible to broad audiences, they also present a danger of repeating the power structures that are implicit in the way many Western archives have traditionally been structured. In her talk Thursday, Elizabeth Maddock Dillon discussed a project that is attempting to avoid this reinscription: the Early Caribbean Digital Archive. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s analysis of the archive as a means of knowledge production and on Ann Laura Stoler’s work on the epistemologies implicit in colonial records, Dillon made a case for a form of archive that deemphasizes the figure of the author, while encouraging a consideration of the complex relations between people, texts, and historical events.

As a way of illustrating some of the problematic features that archives can exhibit, Dillon discussed the Social Networks and Archival Context (SNAC) project. The SNAC Web site includes brief biographical notes about historical figures along with links to related texts in multiple databases. But, as Dillon points out, the people included in the SNAC database are almost all white men—a consequence, she argues, not just of the sources from which the archive draws, but also of the form that it takes. SNAC’s biographical records largely imitate the structure of administrative records, and the way the archive represents the relationships between people and primary texts—drawing a sharp distinction between “creator of” and “referenced in”—places an emphasis on the voices of people who were able to claim authoriality over published works. On account of this structure, the archive tends to privilege the voices of the colonizers over those of the colonized.

Dillon discussed two ways in which the ECDA project attempts to avoid repeating colonial power structures—remix and relationality. By remix, she refers to the idea that images and snippets of text can be presented in contexts that can challenge, rather than reflect, the intentions of the author. As an example, she discussed a story about a slave called Emanuel that appears in a book written by Sir Hans Sloane. According to Sloane, Emanuel feigns an illness, and although he deception is eventually found out, he manages to disrupt the activities of the slavers through the distraction he creates. While Sloane presumably meant the story as a demonstration of his own medical acumen, it can also be read as a demonstration of Emanuel’s knowledge of how to enact resistance against his oppressors. Remix, Dillon argues, offers a way of viewing material in a context that emphasizes the agency of people who are not the authors of primary texts.

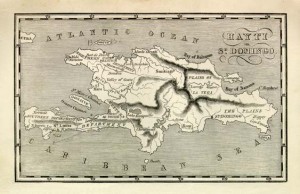

The other strategy that Dillon discussed, relationality, allows for a more complex and polyvalent way of understanding the connections between persons and texts than the notion of authorship. One way ECDA emphasizes relationality is in its use of personography and placeography, the creation of informational records about persons, places, and the relationships between them. The project uses a data model that can account for anonymous persons as well as those represented in colonial records, and that places authors on equal footing with people who are only mentioned in texts.

The other strategy that Dillon discussed, relationality, allows for a more complex and polyvalent way of understanding the connections between persons and texts than the notion of authorship. One way ECDA emphasizes relationality is in its use of personography and placeography, the creation of informational records about persons, places, and the relationships between them. The project uses a data model that can account for anonymous persons as well as those represented in colonial records, and that places authors on equal footing with people who are only mentioned in texts.

Dillon concluded her talk by opening some theoretical questions about the possibility of escaping colonial epistemologies while employing digital technology, and the discussion continued in a similarly theoretical vein. Do the limitations of ECDA’s sources cause it to miss things? Are some of the problems that she discussed “baked in” to digital technologies? Dillon argued that scholarship about the Caribbean can take advantage of the fact that texts often say more than they mean to, which is what enables narratives like the one about Emanuel to be recontextualized as anti-colonial. In response to the question of whether computer technology is inherently problematic, she suggested that the humanities could play a central role in understanding the structures of power that are implicit in technologies. One way that we could do this would be by following the advice with which she ended her talk: that instead of treating a technology like a black box, digital humanists must ask who made the box and what it occludes.