Controversy surrounding some of East Asia’ largest factories has risen in recent years, particularly on the heels of rioting and attempted suicides in plants operated by Foxconn in the Chinese cities of Chengdu and Taiyuan. Joshua Freeman, Distinguished Professor of History at Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center, was inspired to take a deeper look at the cultural significance these “behemoths” hold around the world.

Drawing from a variety of sources, from travel accounts and literature to paintings and photographs, Freeman presented preliminary findings to the Advanced Research Collaborative (ARC) on Thursday, October 9th. Rather than focusing on the singularity of modern Chinese factories, Freeman began with what might be called a genealogy of the gigantic factory, tracing it from its origins in 18th century Britain, through the United States and the Soviet Union in the 19th and early 20th centuries, to the far-flung multinational producers of today’s electronics and consumer goods. To some observers a symbol of progress and national pride, and to others, a symbol of the satanic consequence of hubris, these edifices and the lives of those who operated their machinery have long presented questions and ambiguities.

Freeman’s project begins with simple questions which might bear much more complex answers: Why do we build such big factories in the first place? When and why have state authorities chosen either to concentrate workers in such numbers, or to disperse them into smaller, separate manufactories? How and why have these factories become poles for public discourse?

A brief historical overview reveals a familiar trajectory in Europe and the United States. Industrialists and state supporters saw that larger factories could increase production and profits exponentially. Leftists and conservatives alike often found a certain wonder in these industrial organisms; Freeman reminds us of the photo-journalist Margaret Bourke-White, who once claimed, “The beauty of industry lies in its truth and simplicity.” Some hoped these sites could produce a modern, rational, and even utopian lifestyle among its workers.

Yet there seemed to be a limit to these “Promethean” enterprises: workers, when concentrated in such numbers, would chafe under deteriorating conditions. Gigantic factories had become unwieldy and costly, and eventually attempts were made to disperse manufacturing to more manageable suburban areas.

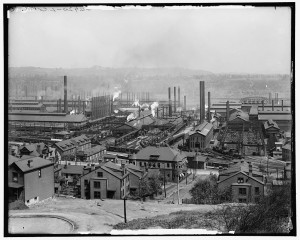

The recent resurgence of gigantic factories in East Asia cannot be explained by a simple “catching up” of “developing” world powers. Like the 19th century nationalists of Britain and Germany, modern governments continue to take pride in building massive projects like dams and bridges. Yet many of today’s largest factories do not evoke the same sort of pride they once might have. Freeman wonders whether this might be a consequence of the goods they produce: from Reebok shoes to iPads, these small products, mostly financed by multinational corporations and sold in foreign markets, are a far cry from the train cars and bridge girders of Pittsburgh’s heyday.

It seems that two overarching dimensions of these factories are at play: size, and location. Freeman’s ongoing work hopes to shed light on deeper layers of these dimensions. One observer noted that size can take many forms: number of workers, number and size of machines, and size of the finished products, for example. Location, too, will introduce enticing complications – to what extent can these “behemoths,” having spread around the world over the past three centuries, be linked together in a way that deepens our understanding of their role in social change and public discourse?