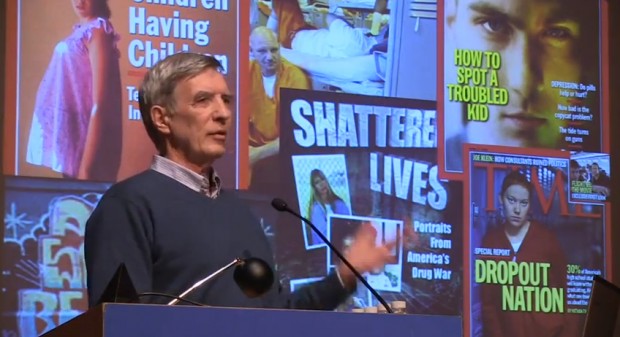

Language and power are tightly intertwined. That was my takeaway from November 16th’s ARC talk featuring the thoughtful, engaged, and critical scholar Tatyana Kleyn, who is an Associate Professor and Director of Bilingual Education and TESOL in the Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture at the City College of New York.

This message about language and power came through in the substance of Kleyn’s talk and the film she screened about how transborder young people navigate language, family, and school as their families repatriate small towns in Oaxaca, Mexico after years of living in the United States. The power of words was also a theme that resonated in the post-talk conversation, including in ways that revealed some tensions in our ARC community that we would do well to address moving forward.

I’ll unpack that conversation in a bit. But first: the talk.

Tatyana is someone I have had the privilege to work with through the CUNY-New York State Initiative on Emergent Bilinguals, a project that brings K-12 teachers, administrators, and professors in bilingual education from across the CUNY campuses together to study and improve education for bilingual kids. As Don mentioned in his opening remarks, Kleyn’s work truly embodies the values and mission of ARC. Her research is interdisciplinary, straddling all of ARC’s clusters. She views phenomena such as immigration and multilingualism through the lens of theories that take into account racial, economic, and linguistic power hierarchies. And she is a public scholar, not content simply to write for narrow audiences of academics. Her films about the experiences of undocumented and transborder youth, as well as curriculum and guides for teachers based on the content of the films, are accessible for free online.

Before showing her film Una Vida, Dos Paìses (One Life, Two Countries), Kleyn asked us to consider the power of film as its own language. She argued persuasively that film can be mobilized as a research method, a medium of dissemination, and as service and activism. At the same time that she celebrated the capacity of the medium to “reprioritize whom we listen to” and to bring research participants’ stories alive for wider audiences, she also described some of the limitations and challenges of this type of scholarship. She has had to build strong relationships with her participants, many of them folks targeted in today’s political climate for their or their family members’ undocumented status. In addition, while she prefers not to use voice-overs in her films so that audiences hear participants “direct from the source,” she acknowledged her and her collaborators’ roles in editing and juxtaposing clips to create cohesive narratives.

The film she screened at ARC introduced us to a group of transborder young people living in Oaxaca, Mexico who call themselves “New Dreamers.” The film captures the complex, mixed emotions that come with “going home” — the feeling of belonging, but also of being “ni de aqui ni de alla” (from neither here nor there). One of the core themes discussed by participants was the role of language in their transitions to life in Mexico. Across contexts in the US and Mexico, languages are used for different purposes and have different statuses attributed to them. While the youth expressed love for the English language, and were often called upon by peers to tutor them in English, they also found themselves lost in classes delivered in Spanish, and felt peers and teachers in Oaxaca sometimes viewed them as stuck-up for their knowledge of English and experiences in the US. In her talk, Kleyn also described how indigenous languages, often regarded as less prestigious in their communities, are a key part of students’ linguistic repertoires, enabling them to communicate especially with older generations.

After Kleyn’s presentation, an audience member asked a question about the young people’s accents. It elicited a strong reaction from some of those present, including one who found it so offensive that he walked out. Rachel Chapman, a fellow ARC student, has provided her take on the question, and her response can be read on our blog here. Kleyn responded by critiquing the premise of the question, arguing that language ideologies about accent are rooted in socially and historically constructed hierarchies that rank speakers based on race, economic status, perceived education, ethnicity, and other markers (see Flores & Rosa, 2015 for more on this).

To me, the strength of ARC is its ability to foster critical conversations about dynamic and complex issues — immigration, inequality, multilingualism, and our digital world — with people at different stages in their academic careers, from different disciplinary, racial, and cultural backgrounds, in order to deepen research and practice in our fields.

Having conversations about complex issues across difference is not easy, however, and this moment at ARC brought those tensions into sharp relief.

Despite a professed desire for open, democratic dialogue, academic communities can reproduce many of the hierarchies they seek to dismantle. As we learned from the student when he returned to the conversation, for people of color, academia can be a violent space. Too often, people of color shoulder the burden and invest much emotional labor into correcting the oppressive dynamics which permeate our institutions. Others (read: white people) need to step up.

At ARC, there are some first steps we can take. There are many incredible organizations such as Border Crossers and the New York Coalition of Radical Educators, among others, which have figured out how to facilitate critical and constructive conversations across difference. I’ve drawn on resources from these organizations as I navigate my role as a white scholar and educator engaged in work with youth of color and their teachers, and have found them exceptionally useful.

To have critical and constructive conversations across difference, relationship-building and setting community norms are key. I noticed that when I began my time as an ARC student, there wasn’t a space devoted to building this community — perhaps such a space could be useful in the future. Some questions for ARC students and fellows to consider as we build community might include:

- What are the challenges of coming together as an interdisciplinary community?

- What norms might help ensure our conversations are both critical and constructive?

- Who gets to study, publish about, and profit from research on inequality, multilingualism, and immigration? Why? In what ways does our community challenge those trends? In what ways does it reproduce them?

- How might ARC fellows and students not just share our research, but work together to ensure we are also engaged in making our fields more equitable and just?

In many ways, Tatyana’s work offers us a compelling example of engaged, critical scholarship. She began her talk by discussing her own positionality — her own background and experiences, and how she arrived to her topic. She is transparent about how her own power and privilege shape her teaching and research. She forges strong bonds with her study participants, reciprocating in the communities that provide her with data. And her scholarship and teaching go hand in hand with her social justice activism.

I hope the talk from this week is a catalyst for some soul-searching at ARC. Not only might we strengthen and deepen our own work, but we might continue the hard work of dismantling oppressive structures within academia too.

Citation:

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149

By Sara Vogel

PhD Student in Urban Education, CUNY-Graduate Center