New Perspectives on Slaveries in the African World

A History Symposium

March 6, 2015

The Skylight Room, 9th floor, room 9100

The Graduate Center, CUNY

On the heels of the international conference on “Slavery in Africa” held in Kenya and Kwasi Konadu’s Transatlantic Africa, which tells the story of transatlantic slaving through African optics and voices, this symposium brings together leading thinkers of global slaveries in the African world to share their work through a full-day of engaged dialogue, offering new perspectives and directions.

This program is sponsored by the Advanced Research Collaborative and the Ph.D Program in History. The symposium is free and open to the public. Seating is limited.

The symposium will be live streamed here.

Breakfast (9 – 10 am)

Welcome (9:45 am)

Helena Rosenblatt

Panel 1: Economics of Slaveries and their Reverberations, (10 am – 12 noon)

Panelists: Catherine Hall, Warren Whatley, Joseph Inikori. Moderated by Kwasi Konadu

Luncheon, (12 – 1 pm)

Panel 2: Theory and Story in the Narration of Slaveries, (12 – 2 pm)

Panelists: James H Sweet, Herman Bennett, Kwasi Konadu. Moderated by C. Daniel Dawson

Panel 3: Atlantic and Indian Ocean Slaveries in Conversation, (2 – 4 pm)

Panelists: Boubacar Barry, Pier Larson, Patrick Harries. Moderated by Megan Vaughan

Abstracts

Panelists

Catherine Hall, Professor of Modern British Social and Cultural History at University College London

New Perspectives on Slavery in the British Atlantic World

In Britain it has been abolition which has been remembered, not colonial slavery. For the last six years we have been developing a project at University College London, “The Legacies of British Slave-ownership.” We have taken slave-owners as the lens through which to bring slavery home to Britain, demonstrating the ways in which the slavery business permeated British society, economy and culture. In this contribution, I will first present the database we have established from the first phase of our project, which focused on the estimated 47,000 claimants for compensation when slavery was abolished in the British Caribbean, Mauritius and the Cape in 1834. We have worked extensively on the legacies of the estimated 3,000 so-called absentees who lived in Britain, demonstrating their commercial, political, cultural and imperial legacies and the part which they played in the making of modern Britain. I will then talk briefly about the second phase of the project, “The structure and significance of British Caribbean slave-ownership 1763-1833,” with a particular focus on my own work on the slave-owners as key figures in the development of racial thinking.

Warren Whatley, Professor of Economics and Faculty of the Center for Afro-American and African Studies at the University of Michigan

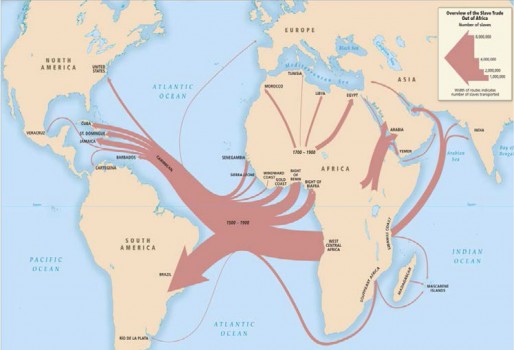

The Economic Legacies of the African Slave Trades

A growing body of evidence is showing that the international slave trade was a significant shock to African economies—one with negative long-term consequences for economic growth. The slave trade was a welfare loss for Africa, which begs the question “why were so many slaves exported?” The main reason is that slave production was organized theft, so by its very nature it generated negative externalities and overproduction—overproduction that was further encouraged by the importation of the gunpowder technology. People fought back, reconfiguring the ways they interacted with each other as insurance against capture. The general trend was towards political decentralization, stronger and more-absolutist local chiefs, more polygyny and a culture of mistrust—all of which reduced long-term growth. These legacies remain developmental challenges for much of sub-Saharan Africa today.

Joseph Inikori, Professor of History of the University of Rochester

The Development of Commercial Agriculture in Pre-Colonial West Africa

This paper focuses on the development of commercial agriculture in pre-colonial West Africa. The evidence shows that subsistence agriculture was overwhelmingly dominant on the eve of European colonial rule. The historical explanation for this long-delayed development of commercial agriculture in the region is the central analytical task in the paper. Given the initial conditions of a predominantly subsistence agricultural economy, sustained long-run population growth and inter-continental trade are identified as the main drivers of the commercializing process in the long run. The analytical task, therefore, boils down to examining the development of these critical factors over long time periods. We find that both factors grew steadily (with some breaks as would be expected) up to the mid-seventeenth century, when population declined absolutely up to the mid-nineteenth century, at the same time that inter-continental trade in West African commodities also declined. The paper argues that these developments explain satisfactorily the delayed development of commercial agriculture during the period of study. We reject arguments in the literature which attribute the decline of population and inter-continental trade to West Africa’s ecology. We argue instead that the violent procurement of millions of captives shipped across the Atlantic and their employment in large scale production of commodities in the Americas for Atlantic commerce—with the abiding support of mercantilist European states—had profound adverse effects on West Africa’s population and the development of the region’s competitiveness in commodity production for Atlantic commerce.

James H. Sweet, Vilas-Jartz Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin, Madison

New Perspectives on Kongo in Revolutionary Haiti

For many scholars, the history of Africans in the Atlantic world only becomes visible at the juncture of the history of the “slave.” However, the sources upon which most of these studies are based, and the organization of the colonial archive more generally operate as something of a trap, inviting researchers to see how African slaves embraced or manipulated colonial institutions and ideas for their own purposes. This paper focuses on methodological and conceptual questions that challenge how historians conduct African-Atlantic history. In particular, I will focus on a French-Kikongo vocabulary published by a French planter ten years after he fled St. Domingue. I will explicate this source in order to achieve two goals: First, by asking the right questions and employing a range of methods, we can find ample evidence of Africans shaping the intellectual history of the Americas. Second, I want to demonstrate how bringing the Africanist’s methodological toolbox to bear on Haitian sources can challenge the very way we understand “slavery” and “revolution” in Haitian history and memory.

Herman Bennett, Professor of History at the CUNY Graduate Center

Sovereigns, Subjects & Slaves

In the century between 1441 and 1540, the subject position of Africans and their descendants who were part and partial of the African diaspora came under scrutiny by Christians. By recognizing the legitimate sovereignty of certain Africans and through the enactment of sovereign power by African lords, Christian traders had to accept prevailing norms, respect governing mores, and in some instance simply acquiesce to the terms Africans dictated in initiating and maintaining trading relations. Africanists have long shown an awareness of this dynamic, known as landlord-strangers relations. But not all lords were respected as sovereigns nor their vassals accorded status as sovereign subjects. “Sovereigns, Subjects, & Slaves” brings into relief how such distinctions arose in the context of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries and the implications these framings had in identifying who legitimately constituted a slave. Stated differently, in the emergent social landscape that accompanied the earliest Iberian-African encounter we glimpse a complex configuration of social differentiation that brings into relief the very making of some Africans into slaves.

Kwasi Konadu, Professor of History and ARC Distinguished CUNY Fellow

Unearthing a “Liberated” African Muslim between Africa and the American Diaspora

This paper unearths and reconstructs the identity of a “liberated” African Muslim from southern Senegambia who left a little known and undeciphered Ajami manuscript. Ajami texts are compositions in African languages that use the Arabic script. As it turns out, available archival records and a translation of this unique manuscript crafted in the African diaspora became critical in locating its author and something about who he was (or could have been), from whence he came, how he eventually reached the Bahamas, and life thereafter. More than coalescing archival fragments, I demonstrate the critical importance of un-silencing (diasporic) African travelers of the Atlantic world, the symbiosis of African and African diaspora histories, and of competencies in African languages in producing such histories.

Boubacar Barry, Professor of History at the Chiekh Anta Diop University, Dakar (Senegal)

New Perspective on Slavery in African World: The Case of Senegambia

Senegambia is a region of convergence and dispersion because of its position at the crossroad of the Sahara, the Sudan and the Atlantic. Therefore, Senegambia was influenced from the beginning by the Tran-Saharan trade and the Atlantic trade, both dominated by the slave trade from the fifteenth century. The continuity and the terminus of the slave trade into the nineteenth century show the importance of the transformation of the societies and region of Senegambia during this period. Beyond the debate over the number of enslaved individuals sold respectively in either direction, our research must emphasize the economic, political and social consequences due to the destabilization of the societies and region of Senegambia that have continued into the present day. The nefarious commerce continues to influence, in a very insidious manner, Senegambian societies through “ethnic” conflicts as well as the violence of the military and militia in the service of corrupt and irresponsible elite. In spite of the existence of many places of memory, such as Gorée or Dufore in Gambia, our destiny is dependent on our capacity to challenge fundamentally the links of dependence and domination, both internally and externally, in connection to the Atlantic economy. The shame of slavery and forced labor still endures. The many civil wars that have given birth to forced migration between states and the clandestine emigration to Europe reminds us the trauma of the slave trade. Beyond the colonial period, we have to return to this long period of five centuries to comprehend the actual making of Africa during those centuries, in addition to the condition and destiny of millions of Africans in the diaspora. The many publications on the traumatic effect of the slave trade and slavery shows the importance of this examination, which is so central in our conscience we, the people on both sides of the Atlantic, cannot sleep. Without any reference to the skin color, the slave trade has bearing on the everyday liberty and prosperity of all of us.

Pier M. Larson, Professor of History and Acting Vice Dean for the Humanities and Social Sciences at The Johns Hopkins University

Antananarivo: Portrait of an Indian Ocean Slaving State

My contribution is a study of enslavement in Madagascar between about 1820 and 1860 by armies of the empire of Antananarivo. It is based on new research in the archives of that empire, which have seldom been employed in writing the history of Madagascar. By analogy, there are relatively few nineteenth century slaving polities in Africa that have left administrative archives testifying to how enslavement proceeded. Those of the empire of Antananarivo offer an understanding of enslavement as administrators of the empire (the slavers) described and explained their actions. The paper examines a number of themes of relevance to both Indian Ocean and Atlantic slaving: the relationship of European oceanic empires to African and Malagasy polities, the seldom explored acts of enslavement generating captives for external and domestic consumption, the relationship of literacy to violence, and similarities as well as differences between slaving in Atlantic and Indian Ocean regions.

Patrick Harries, Professor of African History at the University of Basel (Switzerland)

The Long Middle Passage: Remembering the East African Slave Trade and the Role of the Cape in this Trans-Atlantic Commerce

This presentation concentrates on East Africa’s participation in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and the role of the Cape of Good Hope in this commerce. It starts with a quantification of the trade, concentrating on its spikes and the participation of various exit points on the East African coast. It then moves to examine the organization of the trade and the goods used by various American slavers to assemble their human cargo. A third part examines the changing legal position of the slavers and the growing pressure for abolition in the southwest Indian Ocean. The presentation then looks at Africans as consumers of goods exchanged for slaves, as suppliers of slaves and, most importantly, as human commodities embarked on a long Middle Passage. It concludes by focusing on the estimated 40,000 slaves from East Africa and Madagascar taken to the refreshment station at the Cape, and especially the cultural practices they brought to the region. The presentation closes with a short analysis of the memory of slavery in South Africa, particularly in the Western Cape Province.

Moderators

Kwasi Konadu, Professor of History and ARC Distinguished CUNY Fellow

C. Daniel Dawson, filmmaker, photographer and faculty at Columbia University/New York University

Megan Vaughan, Distinguished Professor of History at the CUNY Graduate Center