In thinking about marronage as an alternative to the more standard narrative of escape to the North that has been codified by the canonization of the slave narrative as the prevailing representation of the US slave experience, voice, and subjectivity, my research is guided by the following overarching questions: What happens to our understanding of slave resistance, collectivity, autonomy, and the geographic coordinates of freedom when we consider representations of maroon slaves and communities in antebellum US fiction?

Sean Gerrity

English Ph.D. Program

The Graduate Center, CUNY

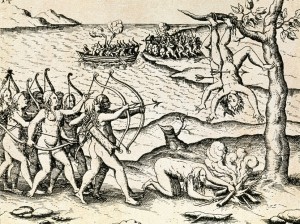

In the broadest sense, my proposed dissertation will examine representations of maroon slaves and maroon communities in antebellum United States fiction. By maroons I mean slaves who escaped their bondage and secluded themselves in the dense, inhospitable, and oftentimes nearly impenetrable swamps and forests of the southern United States, often for many years at a time or permanently. Instead of movements into free states, I am interested in lateral and southerly movements within slaveholding territory to places of relative autonomy where escaped slaves established lives for themselves within the juridical reach of the chattel slavery system but outside of its immediate terror, control, and white domination.

In thinking about marronage as an alternative to the more standard narrative of escape to the North that has been codified by the canonization of the slave narrative as the prevailing representation of the US slave experience, voice, and subjectivity, my research is guided by the following overarching questions: What happens to our understanding of slave resistance, collectivity, autonomy, and the geographic coordinates of freedom when we consider representations of maroon slaves and communities in antebellum US fiction? How do these representations challenge critically entrenched notions of the means for slave freedom as they are articulated by the canonization of the slave narrative and its coupling of literacy with liberty? How do representations of marronage offer alternative ways of imagining the experience of enslavement and the routes to and means of slave freedom and autonomy in antebellum African American writing and writing about enslaved African Americans? By pursuing these questions I aim to complicate the North/South, free/unfree binaristic geographical axis through which enslaved and emancipated black subjectivities have predominantly been imagined in US literary and cultural studies.

I arrived at the archives of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia looking for literary and historical sources related to marronage in Virginia. In particular, I was interested in the Great Dismal Swamp region, estimated to have consisted of over one million acres spanning southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina before human activities like logging, shingle making, and canal building interrupted the ecosystem. A critical consensus exists suggesting that the Great Dismal Swamp was probably home to the highest concentration of maroons at any given time between the colonial and antebellum periods. But the structure of the archive reproduces nineteenth-century strategies for denying the existence of maroons in the United States. By this I mean that the search terms “maroon” and “marronage” will only yield results for twentieth-century secondary sources on maroons because Southerners deliberately avoided these terms when referring to the fugitive inhabitants of the swamps and forests around them. Maroon was a word already associated with militant runaway slave communities in places like Jamaica, Suriname, Haiti, Cuba, and Brazil in the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries, and Southerners had no interest in drawing a parallel between these radically disruptive fugitives and the ones in their midst. Maroons were also ignored by Northern abolitionists, who preferred for a variety of reasons the compellingness and marketability of the slave narrative’s trajectory from descriptions of the brutality of slavery in the South to the advantages of freedom in the North. Thus, maroons only become legible in the archive when we learn to see through the semantic dissembling and deliberate ignorance that have obscured them from view.

This has meant first identifying search terms that will produce archival sources related to what we now call—and should properly be called—US maroons. Working backward from texts like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Dred, Martin Delany’s Blake, and antebellum periodical pieces by David Hunter Strother and Frederick Law Olmstead, among others, which deploy the vocabulary used by Southerners to obliquely describe maroons and their activities, I was able to assemble a preliminary list of such terms. Some examples are: bandit, banditti, truant, fugitive, runaway, outlier, depredations, skulking, and lurking, often in a Boolean search combination with swamp, forest, or “obscure places.” These searches began to produce results, though of course further vetting was needed since words like fugitive and runaway, in particular, were primarily used to refer to runaways in the conventional sense as opposed to maroons as I am defining them.

Some permutation of these terms, the specifics of which I cannot now recall, led me to a text I’d like to elaborate a bit on today, an 1856 play based on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s second antislavery novel, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, published the same year. Entitled Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, A Drama in Four Acts, the work was authored by H.J. Conway, Esq. exclusively for the stage at P.T. Barnum’s American Museum in Manhattan. The printed version of the play was released by New York based John W. Amerman Printers in 1856, and this was the original text I read. A bizarre marriage of an already strange and somewhat episodic, disjointed 600+ page novel featuring a heroically portrayed maroon insurrectionist; the rowdy, mass cultural appeal of Barnum’s entertainment industry; the blackface minstrelsy tradition that had been booming in New York since the 1840s; and the success of stage adaptations of Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, this play’s existence was and remains rather mind boggling to me. It’s hard to imagine just how the crowd on the play’s opening night would have reacted to the titular character Dred clutching the mutilated body of a fellow bondsman who had been killed by slave hunters and proclaiming in unison with his maroon compatriots:

A Brother’s blood! A Brother’s blood,

By cruel white men slain!

Aloud to Heaven it sends a cry,

Shall it cry in vain?

No, no, we swear, [Elevating their rifles]

No, no, we swear,

Just vengeance we decree;

Blood for blood shall be our cry,

We swear on bended knee. [Thunder claps]

A low comedy part was written for some-time Barnum star General Tom Thumb, the “world-renowned and celebrated man in miniature,” whose likeness adorns the cover of the play. Nevertheless, the play is militantly antislavery and we are meant to sympathize with Dred’s plight in a an over the top, melodramatic death scene in which he calls for ruthless vengeance against slave masters and complicit Northerners who acquiesce to the South’s demands. The next stage of my research on the play will focus on its critical and popular reception, and it will be an integral part of my dissertation chapter that uses Dred as its set piece to initiate an exploration of the novel’s cultural work and its impact on the attitudes of the reading public and theater-going populations’ toward maroons and their experiences as a facet of US slavery. Maroons existed as a kind of open secret in Southern society, but citizens’ knowledge of them is harder to assess in the North. For me, this almost entirely forgotten and understudied play will serve as a generative start toward beginning to investigate these questions moving forward.

Busa’s “impossible” project did indeed take a little longer. Over thirty years, the collaboration between the Jesuit and the iconic American firm pushed storage, processing, and retrieval to their technological limit. Given the state of card technology in this era, even data entry for the index took years. Yet the outcome was entirely novel, a “mixed marriage” between computing and linguistic research. The project wrestled with challenges, such as keyword context, that would become central concepts in the field of data analysis. In 1949, not only was IBM flexing its computational muscle with its innovative SSEC mainframe, but its nascent collaboration with Busa prefigured computers that could work not only with numbers, but with words.

Busa’s “impossible” project did indeed take a little longer. Over thirty years, the collaboration between the Jesuit and the iconic American firm pushed storage, processing, and retrieval to their technological limit. Given the state of card technology in this era, even data entry for the index took years. Yet the outcome was entirely novel, a “mixed marriage” between computing and linguistic research. The project wrestled with challenges, such as keyword context, that would become central concepts in the field of data analysis. In 1949, not only was IBM flexing its computational muscle with its innovative SSEC mainframe, but its nascent collaboration with Busa prefigured computers that could work not only with numbers, but with words.