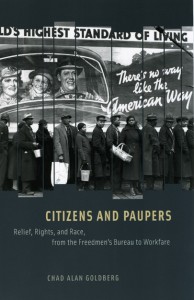

The following interview is with ARC Distinguished Visiting Fellow Chad Alan Goldberg, Professor of Sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. At UW-Madison Goldberg is also affiliated with European Studies, Jewish Studies, and the Mosse Program in History. His primary research interest is the historical sociology of citizenship, broadly understood to include the development of citizenship rights and duties over time, changing levels and forms of civic engagement and political participation, and shifting patterns of civil inclusion and exclusion. He is the author of Citizens and Paupers: Relief, Rights, and Race, from the Freedmen’s Bureau to Workfare (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Question: Please tell us about your research project.

Answer: I’m completing a book that compares the portrayal and meaning of Jews in the French, German, and American sociological traditions from the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. This is the discipline’s formative period, when its fundamental ideas first took shape. Those ideas were a response to the big upheavals that shook Western societies during the long nineteenth century from 1789 and 1914, including democratization, modern industrial capitalism, and urbanization. Sociology’s raison d’être was to interpret and explain the modern world that those upheavals produced. The thesis of my book is that ideas about the Jews formed an important part of the cultural toolkit with which classical sociologists constructed their understanding of modernity in an era of rapid social change. One chapter focuses on the perceived relationship of the Jews to the French Revolution within the French sociological tradition. Another chapter examines the perceived relationship of the Jews to modern industrial capitalism in the German tradition. A third chapter turns to the Chicago School of American sociology, where the key metaphor of modernity was neither democracy nor industrial capitalism, but the city, partly conceived by reference to Jewish immigrants as a quintessentially urban people. I plan to conclude with a chapter that highlights the relevance and implications of the study for the present, particularly in regard to how modernity and European and American identities are defined today.

Q. What is about this research most excites you?

A: I started this project thinking I’d draw on expertise I already have: at the University of Wisconsin, I’ve been teaching classical sociological theory for years, and I’ve been affiliated with Jewish Studies for nearly as long. But in fact, I’ve learned an enormous amount in the course of researching and writing the book. It’s always exciting to have your intellectual horizons expanded that way, and ARC has been a big part of it. My project connects in one way or another to all three of this year’s themes—immigration, inequality, and religion—and my conversations with other fellows and with faculty at the Graduate Center have really stimulated my thinking in fruitful ways. The meaning of American and European modernity today is still constructed in relation to out-groups. New minority groups make up part of that dynamic today; immigration scholars at ARC have provided engaging conversation on this subject, particularly on the importance of Muslim immigrants in Europe. At the same time, I don’t think that Jews have disappeared as a touchstone. At the end of my book I want to draw out these contemporary resonances from my research. Overall, I suggest that we need to not just reflect on the past but to historicize ourselves as contemporary inquirers, regardless of our discipline.

Q: How is this research interdisciplinary?

A: I believe the book will have strong interdisciplinary appeal: it engages scholarship in sociology, Jewish studies, and history, and it is also relevant for scholars in anthropology, cultural studies, and European and American studies. I hope that it will provide some insight and inspiration to other scholars interested in broadly similar questions about the formation of the social sciences, the representation of out-groups, and the uses to which those representations have been put.

Q: What broad implications does this research present for your field?

A: The book is intended both as a study of social theory and as a study in the sociology of ideas. On the one hand, it aims to advance our understanding of classical social theory by situating it more fully in the historical and social context in which it was produced. I want to expand our view of that context to encompass conversations and arguments about the Jews (including depictions that circulated in the public sphere and negative stereotypes promoted by antisemitic and nativist movements), which in my view is an aspect of the context of classical sociology which has not yet been adequately explored. (An important step in that direction is Antisemitism and the Constitution of Sociology, an edited volume to which I contributed a chapter that the University of Nebraska Press will publish this summer.) On the other hand, my project also aims to contribute to the sociology of culture by identifying patterns in how classical sociologists discussed Jews and Judaism, accounting for those patterns, and showing how recurring patterns in social thought (in this case, about Jews) are reproduced over time.

Q: How have your time and experiences at the Advanced Research Collaborative influenced your work?

A: Thanks to the generous support of ARC, I’ve been able to complete a 24,000-word chapter (including notes and references) of my book-in-progress. I’ve also completed two related articles, one submitted to the journal Jewish Social Studies and another commissioned by the editors of the Enzyklopädie jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur. ARC provided valuable time, library resources, and most importantly, opportunities to share and discuss my work with its director Don Robotham, other fellows, and regular CUNY faculty in a creative, intellectually vibrant, interdisciplinary environment. For example, an informal discussion over lunch with another fellow, Mauricio Pietrocola, about the role of cultural schemas in education—a topic seemingly unrelated to my own—helped me to conceptualize the transmission of the intellectual influences about which I’m writing. My work has really benefited from these cross-disciplinary exchanges, and I hope I’ve contributed in equal measure to others’ work. I particularly enjoyed working with the student fellows, who are embarking on interesting and innovative work of their own. Lastly, I would be remiss if I didn’t express my gratitude for the very helpful and capable Assistant Program Officer Alida Rojas and Ally Murphy, without whom my time would not have been nearly as productive or enjoyable.

Q: What’s next? Or what other projects are you working on concurrently?

A: Once this project is completed, I’d like to embark on an intellectual biography of Horace Kallen, a twentieth-century American intellectual best known as the architect of cultural pluralism in the Progressive era. This is an interest that partly comes out of my chapter on the American sociological tradition. I’m interested in exploring how Kallen negotiated the tension between his commitment to cultural pluralism and the ideal of a common democratic culture promoted by the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey, who exercised an important intellectual influence on him. It seems to me that we’re still struggling with that tension today, so a historical study of Kallen’s thought would very much speak to contemporary concerns.

Q: Finally, where do you hope your field is headed? What do you look forward to seeing more of?

A: Sociology is a very big tent, and it’s pulled in competing directions because like all social sciences it occupies an intermediary position between the “hard” sciences and the humanities. As a result, sociology is always galloping off in multiple directions at once. But I hope my work will encourage younger scholars to see the value of the discipline’s historical and humanistic wing and to take up that kind of social inquiry.

—